History of India

This article is about the history of the Indian subcontinent prior to the partition of India in 1947. For the modern Republic of India, see History of the Republic of India. For Pakistan and Bangladesh, see History of Pakistan and History of Bangladesh.

"Indian history" redirects here. For other uses, see Native American history.

|

|---|

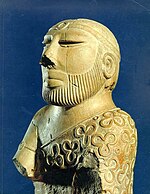

The history of India begins with evidence of human activity of Homo sapiens as long as 75,000 years ago, or with earlier hominids includingHomo erectus from about 500,000 years ago.[1] The Indus Valley Civilisation, which spread and flourished in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent from c. 3300 to 1300 BCE in present-day Pakistan and northwest India, was the first major civilisation in South Asia.[2] A sophisticated and technologically advanced urban culture developed in the Mature Harappan period, from 2600 to 1900 BCE.[3]

This Bronze Age civilisation collapsed before the end of the second millennium BCE and was followed by the Iron Age Vedic Civilisation, which extended over much of the Indo-Gangetic plain and which witnessed the rise of major polities known as the Mahajanapadas. In one of these kingdoms, Magadha, Mahavira and Gautama Buddha were born in the 6th or 5th century BCE and propagated their Shramanic philosophies.

Most of the subcontinent was conquered by the Maurya Empire during the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE. Various parts of India ruled by numerous Middle kingdoms for the next 1,500 years, among which the Gupta Empire stands out. Southern India saw the rule of theChalukyas, Cholas, Pallavas, and Pandyas. This period, witnessing a Hindu religious and intellectual resurgence, is known as the classical or "Golden Age of India". During this period, aspects of Indian civilisation, administration, culture, and religion (Hinduism and Buddhism) spread to much of Asia, while kingdoms in southern India had maritime business links with the Roman Empire from around 77 CE.

Muslim rule in the subcontinent began in 8th century CE when the Arab general Muhammad bin Qasim conquered Sindh and Multan in southern Punjab in modern day Pakistan,[4] setting the stage for several successive invasions from Central Asia between the 10th and 15th centuries CE, leading to the formation of Muslim empires in the Indian subcontinent such as the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire. Mughal rule came from Central Asia to cover most of the northern parts of the subcontinent. Mughal rulers introduced Central Asian art and architecture to India. In addition to the Mughals and various Rajput kingdoms, several independent Hindu states, such as the Vijayanagara Empire, the Maratha Empire, Eastern Ganga Empire and the Ahom Kingdom, flourished contemporaneously in southern, western, eastern andnortheastern India respectively. The Mughal Empire suffered a gradual decline in the early 18th century, which provided opportunities for theAfghans, Balochis, Sikhs, and Marathas to exercise control over large areas in the northwest of the subcontinent until the British East India Company gained ascendancy over South Asia.[5]

Beginning in the mid-18th century and over the next century, large areas of India were annexed by the British East India Company. Dissatisfaction with Company rule led to the Indian Rebellion of 1857, after which the British provinces of India were directly administered by the British Crown and witnessed a period of both rapid development of infrastructure and economic decline. During the first half of the 20th century, a nationwide struggle for independence was launched by the Indian National Congress and later joined by the Muslim League. The subcontinent gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1947, after the British provinces were partitioned into the dominions of India and Pakistan and the princely states all acceded to one of the new states.

Periodisation[edit]

James Mill (1773-1836), in his The History of British India (1817),[6] distinguished three phases in the history of India, namely Hindu, Muslim and British civilisations.[6][7] This periodisation has been criticised, for the misconceptions it has given rise to.[8] Another periodisation is the division into "ancient, classical, medieaval and modern periods".[9]Smart[10] and Michaels[11] seem to follow Mill's periodisation,[note 1], while Flood[12] and Muesse[14][15] follow the "ancient, classical, medieaval and modern periods" periodisation.[16]

Different periods are designated as "classical Hinduism":

- Smart calls the period between 1000 BCE and 100 CE "pre-classical". It's the formative period for the Upanishads and Brahmanism[note 2], Jainism and Buddhism. For Smart, the "classical period" lasts from 100 to 1000 CE, and coincides with the flowering of "classical Hinduism" and the flowering and deterioration of Mahayana-buddhism in India.[18]

- For Michaels, the period between 500 BCE and 200 BCE is a time of "Ascetic reformism"[19], whereas the period between 200 BCE and 1100 CE is the time of "classical Hinduism", since there is "a turning point between the Vedic religion and Hindu religions".[20]

- Muesse discerns a longer period of change, namely between 800 BCE and 200 BCE, which he calls the "Classical Period":

...this was a time when traditional religious practices and beliefs were reassessed. The brahmins and the rituals they performed no longer enjoyed the same prestige they had in the Vedic pariod".[21]

According to Muesse, some of the fundamental concepts of Hinduism, namely karma, reincarnation and "personal enlightenment and transformation", which did not exist in the Vedic religion, developed in this time:

Indian philosophers came to regard the human as an immortal soul encased in a perishable body and bound by action, or karma, to a cycle of endless existences.[22]

According to Muesse, reincarnation is "a fundamental principle of virtually all religions formed in Indias".[23]

The period of the ascetic reforms saw the rise of Buddhism and Jainism, while Sikhism originated during the time of Islamic rule.[24]

| Smart[10] | Michaels (overall)[24] | Michaels (detailed)[24] | Muesse[15] | Flood[25] |

| Indus Valley Civilisation and Vedic period (ca. 3000-1000 BCE) | Prevedic religions (until ca. 1750 BCE)[11] | Prevedic religions (until ca. 1750 BCE)[11] | Indus Valley Civilization (3300–1400 BCE) | Indus Valley Civilisation (ca. 2500 to 1500 BCE) |

| Vedic religion (ca. 1750-500 BCE) | Early Vedic Period (ca. 1750-1200 BCE) | Vedic Period (1600–800 BCE) | Vedic period (ca. 1500-500 BCE) | |

| Middle Vedic Period (from 1200 BCE) | ||||

| Pre-classical period (ca. 1000 BCE - 100 CE) | Late Vedic period (from 850 BCE) | Classical Period (800–200 BCE) | ||

| Ascetic reformism (ca. 500-200 BCE) | Ascetic reformism (ca. 500-200 BCE) | Epic and Puranic period (ca. 500 BCE to 500 CE) | ||

| Classical Hinduism (ca. 200 BCE-1100 CE)[20] | Preclassical Hinduism (ca. 200 BCE-300 CE)[26] | Epic and Puranic period (200 BCE–500 CE) | ||

| Classical period (ca. 100 CE - 1000 CE) | "Golden Age" (Gupta Empire) (ca. 320-650 CE)[27] | |||

| Late-Classical Hinduism (ca. 650-1100 CE)[28] | Medieval and Late Puranic Period (500–1500 CE) | Medieval and Late Puranic Period (500–1500 CE) | ||

| Hindu-Islamic civilisation (ca. 1000-1750 CE) | Islamic rule and "Sects of Hinduism" (ca. 1100-1850 CE)[29] | Islamic rule and "Sects of Hinduism" (ca. 1100-1850 CE)[29] | ||

| Modern Age (1500–present) | Modern period (ca. 1500 CE to present) | |||

| Modern period (ca. 1750 CE - present) | Modern Hinduism (from ca. 1850)[30] | Modern Hinduism (from ca. 1850)[30] |

Prehistoric era[edit]

Stone Age[edit]

Main article: South Asian Stone Age

Isolated remains of Homo erectus in Hathnora in the Narmada Valley in central India indicate that India might have been inhabited since at least the Middle Pleistocene era, somewhere between 500,000 and 200,000 years ago.[31][32] Tools crafted by proto-humans that have been dated back two million years have been discovered in the northwestern part of the subcontinent.[33][34] The ancient history of the region includes some of South Asia's oldest settlements[35] and some of its major civilisations.[36][37] The earliest archaeological site in the subcontinent is the palaeolithic hominid site in the Soan River valley.[38] Soanian sites are found in the Sivalik region across what are now India, Pakistan, and Nepal.[39]

The Mesolithic period in the Indian subcontinent was followed by the Neolithic period, when more extensive settlement of the subcontinent occurred after the end of the last Ice Age approximately 12,000 years ago. The first confirmed semipermanent settlements appeared 9,000 years ago in the Bhimbetka rock shelters in modern Madhya Pradesh, India. Early Neolithic culture in South Asia is represented by theBhirrana findings (7500 BCE)in Haryana, India & Mehrgarh findings (7000 BCE onwards) in Balochistan, Pakistan.[40][41]

Traces of a Neolithic culture have been alleged to be submerged in the Gulf of Khambat in India, radiocarbon dated to 7500 BCE.[42]However, the one dredged piece of wood in question was found in an area of strong ocean currents. Neolithic agriculture cultures sprang up in the Indus Valley region around 5000 BCE, in the lower Gangetic valley around 3000 BCE, and in later South India, spreading southwards and also northwards into Malwa around 1800 BCE. The first urban civilisation of the region began with the Indus Valley Civilisation.[43]

Bronze Age[edit]

Main article: Indus Valley Civilisation

The Bronze Age in the Indian subcontinent began around 3300 BCE with the early Indus Valley Civilisation. It was centred on the Indus Riverand its tributaries which extended into the Ghaggar-Hakra River valley,[36] the Ganges-Yamuna Doab,[44] Gujarat,[45] and southeasternAfghanistan.[46]

The civilisation is primarily located in modern-day India (Gujarat, Haryana, Punjab and Rajasthan provinces) and Pakistan (Sindh, Punjab, and Balochistan provinces). Historically part of Ancient India, it is one of the world's earliest urban civilisations, along with Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt.[47] Inhabitants of the ancient Indus river valley, the Harappans, developed new techniques in metallurgy and handicraft (carneol products, seal carving), and produced copper, bronze, lead, and tin.

The Mature Indus civilisation flourished from about 2600 to 1900 BCE, marking the beginning of urban civilisation on the subcontinent. The civilisation included urban centres such as Dholavira, Kalibangan, Rupar, Rakhigarhi, and Lothal in modern-day India, and Harappa, Ganeriwala, and Mohenjo-daro in modern-day Pakistan. The civilisation is noted for its cities built of brick, roadside drainage system, and multistoried houses.

Vedic period (1500–500 BCE)[edit]

Main article: Vedic Civilisation

See also: Vedas and Indo-Aryans

The Vedic period is characterised by Indo-Aryan culture associated with the texts of Vedas, sacred to Hindus, which were orally composed in Vedic Sanskrit. The Vedas are some of the oldest extant texts in India[48] and next to some writings in Egypt and Mesopotamia are the oldest in the world. The Vedic period lasted from about 1500 to 500 BCE,[49] laying the foundations of Hinduism and other cultural aspects of early Indian society. In terms of culture, many regions of the subcontinent transitioned from the Chalcolithic to the Iron Age in this period.[50]

Vedic society[edit]

Historians have analysed the Vedas to posit a Vedic culture in the Punjab region and the upper Gangetic Plain.[50]Most historians also consider this period to have encompassed several waves of Indo-Aryan migration into the subcontinent from the north-west.[51][52] Vedic people believed in the transmigration of the soul, and the peepultree and cow were sanctified by the time of the Atharva Veda.[53] Many of the concepts of Indian philosophy espoused later like Dharma, Karma etc. trace their root to the Vedas.[54]

Early Vedic society consisted of largely pastoral groups, with late Harappan urbanisation having been abandoned.[55] After the time of the Rigveda, Aryan society became increasingly agricultural and was socially organised around the four varnas, or social classes. In addition to the Vedas, the principal texts of Hinduism, the core themes of the Sanskrit epics Ramayana and Mahabharata are said to have their ultimate origins during this period.[56] The Mahabharata remains, today, the longest single poem in the world.[57] The events described in the Ramayana are from a later period of history than the events of the Mahabharata.[58] The early Indo-Aryan presence probably corresponds, in part, to the Ochre Coloured Pottery culture in archaeological contexts.[59]

Sanskritization[edit]

Main article: Sanskritization

Since Vedic times, "people from many strata of society throughout the subcontinent tended to adapt their religious and social life to Brahmanic norms", a process sometimes called Sanskritization.[60] It is reflected in the tendency to identify local deities with the gods of the Sanskrit texts.[60]

The Kuru kingdom[61] corresponds to the Black and Red Ware and Painted Grey Ware cultures and to the beginning of the Iron Age in northwestern India, around 1000 BCE, as well as with the composition of the Atharvaveda, the first Indian text to mention iron, as śyāma ayas, literally "black metal." The Painted Grey Ware culture spanned much of northern India from about 1100 to 600 BCE.[59] The Vedic Period also established republics such as Vaishali, which existed as early as the 6th century BCE and persisted in some areas until the 4th century CE. The later part of this period corresponds with an increasing movement away from the previous tribal system towards the establishment of kingdoms, called mahajanapadas.

Formative period (800-200 BCE)[edit]

During the time between 800 and 200 BCE the Shramana-movement developed, from which originated Jainism and Buddhism. In the same period the first Upanishds were written.

Mahajanapadas (600-300 BCE)[edit]

Main articles: Mahajanapadas and Haryanka dynasty

In the later Vedic Age, a number of small kingdoms or city states had covered the subcontinent, many mentioned in Vedic, early Buddhist and Jaina literature as far back as 1000 BCE. By 500 BCE, sixteen monarchies and "republics" known as the Mahajanapadas—Kashi, Kosala, Anga, Magadha, Vajji (or Vriji), Malla, Chedi, Vatsa (or Vamsa), Kuru, Panchala, Matsya (or Machcha), Shurasena, Assaka, Avanti, Gandhara,and Kamboja—stretched across the Indo-Gangetic Plain from modern-day Afghanistan to Bengal and Maharastra. This period saw the second major rise of urbanism in India after the Indus Valley Civilisation.[62]

Many smaller clans mentioned within early literature seem to have been present across the rest of the subcontinent. Some of these kings were hereditary; other states elected their rulers. The educated speech at that time was Sanskrit, while the languages of the general population of northern India are referred to as Prakrits. Many of the sixteen kingdoms had coalesced to four major ones by 500/400 BCE, by the time of Gautama Buddha. These four were Vatsa, Avanti, Kosala, and Magadha.[62]

Upanishads and Shramana movements[edit]

See also: Gautama Buddha and Mahavira

Further information: Upanishads, Indian Religions, Indian philosophy, and Ancient universities of India

The 9th and 8th centuries BCE witnessed the composition of the earliest Upanishads.[63]:183 Upanishads form the theoretical basis of classical Hinduism and are known as Vedanta (conclusion of the Vedas).[64] The older Upanishads launched attacks of increasing intensity on the ritual. Anyone who worships a divinity other than the Self is called a domestic animal of the gods in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. The Mundaka launches the most scathing attack on the ritual by comparing those who value sacrifice with an unsafe boat that is endlessly overtaken by old age and death.[65]

Increasing urbanisation of India in 7th and 6th centuries BCE led to the rise of new ascetic or shramana movements which challenged the orthodoxy of rituals.[66] Mahavira (c. 549–477 BCE), proponent of Jainism, and Buddha (c. 563-483), founder of Buddhism were the most prominent icons of this movement. Shramana gave rise to the concept of the cycle of birth and death, the concept of samsara, and the concept of liberation.[67] Buddha found a Middle Way that ameliorated the extreme asceticism found in the Sramana religions.[68]

Around the same time, Mahavira (the 24th Tirthankara in Jainism) propagated a theology that was to later become Jainism.[69] However, Jain orthodoxy believes the teachings of the Tirthankaras predates all known time and scholars believe Parshva, accorded status as the 23rd Tirthankara, was a historical figure. The Vedas are believed to have documented a few Tirthankaras and an ascetic order similar to theshramana movement.[70]

Persian and Greek conquests[edit]

See also: Achaemenid Empire, Greco-Buddhism, Indo-Greek Kingdom, Alexander the Great, Nanda Empire, and Gangaridai

In 530 BCE Cyrus the Great, King of the Persian Achaemenid Empire crossed the Hindu-Kush mountains to seek tribute from the tribes of Kamboja, Gandhara and the trans-India region.[71] By 520 BCE, during the reign of Darius I of Persia, much of the northwestern subcontinent (present-day eastern Afghanistan and Pakistan) came under the rule of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. The area remained under Persian control for two centuries.[72] During this time India supplied mercenaries to the Persian army then fighting in Greece.[71]

Under Persian rule the famous city of Takshashila became a centre where both Vedic and Iranian learning were mingled.[73] The impact of Persian ideas was felt in many areas of Indian life. Persian coinage and rock inscriptions were copied by India. However, Persian ascendency in northern India ended with Alexander the Great's conquest of Persia in 327 BCE.[74]

By 326 BCE, Alexander the Great had conquered Asia Minor and the Achaemenid Empire and had reached the northwest frontiers of the Indian subcontinent. There he defeated King Porus in the Battle of the Hydaspes (near modern-day Jhelum, Pakistan) and conquered much of the Punjab.[75] Alexander's march east put him in confrontation with the Nanda Empire of Magadha and the Gangaridai Empire of Bengal. His army, exhausted and frightened by the prospect of facing larger Indian armies at the Ganges River, mutinied at the Hyphasis (modernBeas River) and refused to march further East. Alexander, after the meeting with his officer, Coenus, and learning about the might of Nanda Empire, was convinced that it was better to return.

The Persian and Greek invasions had important repercussions on Indian civilisation. The political systems of the Persians were to influence future forms of governance on the subcontinent, including the administration of the Mauryan dynasty. In addition, the region of Gandhara, or present-day eastern Afghanistan and northwest Pakistan, became a melting pot of Indian, Persian, Central Asian, and Greek cultures and gave rise to a hybrid culture, Greco-Buddhism, which lasted until the 5th century CE and influenced the artistic development of Mahayana Buddhism.

Maurya Empire (322–185 BCE)[edit]

Main article: Maurya Empire

The Maurya Empire (322–185 BCE), ruled by the Mauryan dynasty, was a geographically extensive and powerful political and military empire in ancient India. The empire was established by Chandragupta Maurya in Magadhawhat is now Bihar.[76] The empire flourished under the reign of Ashoka the Great.[77]

At its greatest extent, it stretched to the north to the natural boundaries of the Himalayas and to the east into what is now Assam. To the west, it reached beyond modern Pakistan, annexing Balochistan and much of what is nowAfghanistan, including the modern Herat and Kandahar provinces. The empire was expanded into India's central and southern regions by the emperors Chandragupta and Bindusara, but it excluded extensive unexplored tribal and forested regions near Kalinga which were subsequently taken by Ashoka.[78]

Ashoka ruled the Maurya Empire for 37 years from 268 BCE until he died in 232 BCE.[78] During that time, Ashoka pursued an active foreign policy aimed at setting up a unified state.[79] However, Ashoka became involved in a war with the state of Kalinga which is located on the western shore of the Bay of Bengal.[80] This war forced Ashoka to abandon his attempt at a foreign policy which would unify the Maurya Empire.[81]

During the Mauryan Empire slavery developed rapidly and significant amount of written records on slavery are found.[82] The Mauryan Empire was based on a modern and efficient economy and society. However, the sale of merchandise was closely regulated by the government.[83] Although there was no banking in the Mauryan society, usury was customary with loans made at the recognized interest rate of 15% per annum.

Ashoka's reign propagated Buddhism. In this regard Ashoka established many Buddhist monuments. Indeed, Ashoka put a strain on the economy and the government by his strong support of Buddhism. towards the end of his reign he "bled the state coffers white with his generous gifts to promote the promulation of Buddha's teaching.[84] As might be expected, this policy caused considerable opposition within the government. This opposition rallied around Sampadi, Ashoka's grandson and heir to the throne.[85] Religious opposition to Ashoka also arose among the orthodox Brahmanists and the adherents of Jainism.[86]

Chandragupta's minister Chanakya wrote the Arthashastra, one of the greatest treatises on economics, politics, foreign affairs, administration, military arts, war, and religion produced in Asia. Archaeologically, the period of Mauryan rule in South Asia falls into the era of Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW). The Arthashastra and the Edicts of Ashoka are primary written records of the Mauryan times. The Lion Capital of Asoka at Sarnath, is the national emblem of India.

Epic and Early Puranic Period - Early Classical Period & Golden Age (ca. 200 BCE–700 CE)[edit]

Main article: Middle Kingdoms of India

The time between 200 BCE and ca. 1100 CE is the "Classical Age" of India. It can be divided in various sub-periods, depending on the chosen periodisation. The Gupta Empire (4th-6th century) is regarded as the "Golden Age" of Hinduism, but a host of kingdoms ruled over India in these centuries.

The Satavahana dynasty, also known as the Andhras, ruled in southern and central India after around 230 BCE. Satakarni, the sixth ruler of the Satvahana dynasty, defeated theSunga Empire of north India. Afterwards, Kharavela, the warrior king of Kalinga,[87] ruled a vast empire and was responsible for the propagation of Jainism in the Indian subcontinent.[87]

The Kharavelan Jain empire included a maritime empire with trading routes linking it to Sri Lanka, Burma, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia, Borneo, Bali, Sumatra, and Java. Colonists from Kalinga settled in Sri Lanka, Burma, as well as the Maldives and Maritime Southeast Asia. The Kuninda Kingdom was a small Himalayan state that survived from around the 2nd century BCE to the 3rd century CE.

The Kushanas migrated from Central Asia into northwestern India in the middle of the 1st century CE and founded an empire that stretched from Tajikistan to the middle Ganges. The Western Satraps (35-405 CE) were Saka rulers of the western and central part of India. They were the successors of the Indo-Scythians and contemporaries of the Kushans who ruled the northern part of the Indian subcontinent and the Satavahana (Andhra) who ruled in central and southern India.

Different dynasties such as the Pandyans, Cholas, Cheras, Kadambas, Western Gangas, Pallavas, and Chalukyas, dominated the southern part of the Indian peninsula at different periods of time. Several southern kingdoms formed overseas empires that stretched into Southeast Asia. The kingdoms warred with each other and the Deccan states for domination of the south. The Kalabras, a Buddhist dynasty, briefly interrupted the usual domination of the Cholas, Cheras, and Pandyas in the south.

Northwestern hybrid cultures[edit]

The northwestern hybrid cultures of the subcontinent included the Indo-Greeks, the Indo-Scythians, the Indo-Parthians, and the Indo-Sassinids. The first of these, the Indo-Greek Kingdom, was founded when the Greco-Bactrian king Demetrius invaded the region in 180 BCE, extending his rule over various parts of present-day Afghanistan and Pakistan. Lasting for almost two centuries, the kingdom was ruled by a succession of more than 30 Greek kings, who were often in conflict with each other.

The Indo-Scythians were a branch of the Indo-European Sakas (Scythians) who migrated from southern Siberia, first into Bactria, subsequently intoSogdiana, Kashmir, Arachosia, and Gandhara, and finally into India. Their kingdom lasted from the middle of the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century BCE.

Yet another kingdom, the Indo-Parthians (also known as the Pahlavas), came to control most of present-day Afghanistan and northern Pakistan, after fighting many local rulers such as the Kushan ruler Kujula Kadphises, in the Gandhara region. The Sassanid empire of Persia, who was contemporaneous with the Gupta Empire, expanded into the region of present-day Balochistan in Pakistan, where the mingling of Indian culture and the culture of Iran gave birth to a hybrid culture under the Indo-Sassanids.

Kushan Empire[edit]

Main article: Kushan Empire

The Kushan Empire expanded out of what is now Afghanistan into the northwest of the subcontinent under the leadership of their first emperor, Kujula Kadphises, about the middle of the 1st century CE. By the time of his grandson, Kanishka, (whose era is thought to have begun c. 127 CE), they had conquered most of northern India, at least as far as Saketaand Pataliputra, in the middle Ganges Valley, and probably as far as the Bay of Bengal.[88]

They played an important role in the establishment of Buddhism in India and its spread to Central Asia and China. By the 3rd century, their empire in India was disintegrating; their last known great emperor being Vasudeva I (c. 190-225 CE).

Roman trade with India[edit]

Main article: Roman trade with India

Roman trade with India started around 1 CE, during the reign of Augustus and following his conquest of Egypt, which had been India's biggest trade partner in the West.

The trade started by Eudoxus of Cyzicus in 130 BCE kept increasing, and according to Strabo (II.5.12.[89]), by the time of Augustus, up to 120 ships set sail every year from Myos Hormos on the Red Sea to India. So much gold was used for this trade, and apparently recycled by the Kushans for their own coinage, that Pliny the Elder (NH VI.101) complained about the drain of specie to India:

"India, China and the Arabian peninsula take one hundred million sesterces from our empire per annum at a conservative estimate: that is what our luxuries and women cost us. For what percentage of these imports is intended for sacrifices to the gods or the spirits of the dead?"—Pliny, Historia Naturae 12.41.84.[90]

The maritime (but not the overland) trade routes, harbours, and trade items are described in detail in the 1st century CE Periplus of the Erythraean Sea.

Gupta rule - Golden Age[edit]

Main article: Gupta Empire

Further information: Meghadūta, Abhijñānaśākuntala, Kumārasambhava, Panchatantra, Aryabhatiya, Indian numerals, and Kama Sutra

The Classical Age refers to the period when much of the Indian subcontinent was reunited under the Gupta Empire (c. 320–550 CE).[91][92] This period has been called the Golden Age of India[93] and was marked by extensive achievements in science, technology,engineering, art, dialectic, literature, logic, mathematics, astronomy, religion, and philosophy that crystallized the elements of what is generally known as Hindu culture.[94] The decimal numeral system, including the concept of zero, was invented in India during this period.[95] The peace and prosperity created under leadership of Guptas enabled the pursuit of scientific and artistic endeavors in India.[96]

The high points of this cultural creativity are magnificent architecture, sculpture, and painting.[97] The Gupta period produced scholars such as Kalidasa, Aryabhata, Varahamihira, Vishnu Sharma, and Vatsyayana who made great advancements in many academic fields.[98]Science and political administration reached new heights during the Gupta era. Strong trade ties also made the region an important cultural centre and established it as a base that would influence nearby kingdoms and regions in Burma, Sri Lanka, Maritime Southeast Asia, and Indochina.

The Gupta period marked a watershed of Indian culture: the Guptas performed Vedic sacrifices to legitimize their rule, but they also patronized Buddhism, which continued to provide an alternative to Brahmanical orthodoxy. The military exploits of the first three rulers—Chandragupta I (c. 319–335), Samudragupta (c. 335–376), and Chandragupta II (c. 376–415) —brought much of India under their leadership.[99] They successfully resisted the northwestern kingdoms until the arrival of the Hunas, who established themselves in Afghanistan by the first half of the 5th century, with their capital at Bamiyan.[100] However, much of the Deccan and southern India were largely unaffected by these events in the north.[101][102]

Medieval and Late Puranic Period - Late-Classical Age (500–1500 CE)[edit]

Main articles: Middle Kingdoms of India, Badami Chalukyas, Rashtrakuta, Eastern Ganga dynasty, Western Chalukyas, Rajput kingdoms, and Vijayanagara Empire

The "Late-Classical Age"[28] in India began after the end of the Gupta Empire[28] and the collapse Harsha Empire in the 7th century CE[28], and ended with the fall of the Vijayanagara Empire in the south in the 13th century, due to pressure from Islamic invaders[29] to the north.

This period produced some of India's finest art, considered the epitome of classical development, and the development of the main spiritual and philosophical systems which continued to be in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism. King Harsha of Kannauj succeeded in reuniting northern India during his reign in the 7th century, after the collapse of the Gupta dynasty. His kingdom collapsed after his death.

Central Asian and North Western Indian Buddhism weakened in the 6th century after the White Huninvasion, who followed their own religions such as Tengri, and Manichaeism. Muhammad bin Qasim's invasion of Sindh in 711 CE witnessed further decline of Buddhism. The Chach Nama records many instances of conversion of stupas to mosques such as at Nerun[103]

In 7th century CE, Kumārila Bhaṭṭa formulated his school of Mimamsa philosophy and defended the position on Vedic rituals against Buddhist attacks. Scholars note Bhaṭṭa's contribution to the decline of Buddhism.[104] His dialectical success against the Buddhists is confirmed by Buddhist historianTathagata, who reports that Kumārila defeated disciples of Buddhapalkita, Bhavya, Dharmadasa, Dignaga and others.[105]

Ronald Inden writes that by 8th century BCE symbols of Hindu gods "replaced the Buddha at the imperial centre and pinnacle of the cosmo-political system, the image or symbol of the Hindu god comes to be housed in a monumental temple and given increasingly elaborate imperial-style puja worship".[106] Although Buddhism did not disappear from India for several centuries after the eighth, royal proclivities for the cults of Vishnu and Shiva weakened Buddhism's position within the sociopolitical context and helped make possible its decline.[107]

Northern India[edit]

From the 7th to the 9th century, three dynasties contested for control of northern India: the Gurjara Pratiharas of Malwa,the Eastern Ganga dynasty of Odisha, the Palas of Bengal, and the Rashtrakutas of the Deccan. The Sena dynasty would later assume control of the Pala Empire, and the Gurjara Pratiharas fragmented into various states. These were the first of the Rajput states, a series of kingdoms which managed to survive in some form for almost a millennium, until Indian independence from the British. The first recorded Rajput kingdoms emerged in Rajasthan in the 6th century, and small Rajput dynasties later ruled much of northern India. One Gurjar[108][109] Rajput of theChauhan clan, Prithvi Raj Chauhan, was known for bloody conflicts against the advancing Islamic sultanates. The Shahi dynasty ruled portions of eastern Afghanistan, northern Pakistan, and Kashmir from the mid-7th century to the early 11th century.

The Chalukya dynasty ruled parts of southern and central India from Badami in Karnataka between 550 and 750, and then again fromKalyani between 970 and 1190. The Pallavas of Kanchipuram were their contemporaries further to the south. With the decline of the Chalukya empire, their feudatories, the Hoysalas of Halebidu, Kakatiyas of Warangal, Seuna Yadavas of Devagiri, and a southern branch of the Kalachuri, divided the vast Chalukya empire amongst themselves around the middle of 12th century.

The Chola Empire at its peak covered much of the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. Rajaraja Chola I conquered all of peninsular south India and parts of Sri Lanka. Rajendra Chola I's navies went even further, occupying coasts from Burma to Vietnam,[110] the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, the Lakshadweep (Laccadive) islands, Sumatra, and the Malay Peninsula in Southeast Asia and the Pegu islands. Later during the middle period, the Pandyan Empire emerged in Tamil Nadu, as well as the Chera Kingdom in parts of Kerala and Tamil Nadu. By 1343, last of these dynasties had ceased to exist, giving rise to the Vijayanagar empire.

The ports of south India were engaged in the Indian Ocean trade, chiefly involving spices, with the Roman Empire to the west and Southeast Asia to the east.[111][112] Literature in local vernaculars and spectacular architecture flourished until about the beginning of the 14th century, when southern expeditions of the sultan of Delhi took their toll on these kingdoms. The Hindu Vijayanagar Empire came into conflict with the Islamic Bahmani Sultanate, and the clashing of the two systems caused a mingling of the indigenous and foreign cultures that left lasting cultural influences on each other.

The Islamic Sultanates[edit]

Main articles: Muslim conquest of India, Islamic Empires in India, Bahmani Sultanate, and Deccan Sultanates

After conquering Persia, the Arab Umayyad Caliphate incorporated parts of what is now Pakistan around 720. The Muslim rulers were keen to invade India,[113] a rich region with a flourishing international trade and the only known diamond mines in the world.[114] In 712, Arab Muslim general Muhammad bin Qasim conquered most of the Indus region in modern day Pakistan for the Umayyad empire, incorporating it as the "As-Sindh" province with its capital at Al-Mansurah, 72 km (45 mi) north of modern Hyderabad in Sindh, Pakistan. After several wars, the Hindu Rajput clans defeated the Arabs at the Battle of Rajasthan, halting their expansion and containing them at Sindh in Pakistan.[115]Many short-lived Islamic kingdoms (sultanates) under foreign rulers were established across the north western subcontinent over a period of a few centuries. Additionally, Muslim trading communities flourished throughout coastal south India, particularly on the western coast where Muslim traders arrived in small numbers, mainly from the Arabian peninsula. This marked the introduction of a third Abrahamic Middle Eastern religion, following Judaism and Christianity, often in puritanical form. Later, the Bahmani Sultanate and Deccan sultanates, founded by Turkic rulers, flourished in the south.

The Vijayanagara Empire rose to prominence by the end of the 13th century as a culmination of attempts by the southern powers to ward offIslamic invasions. The empire dominated all of Southern India and fought off invasions from the five established Deccan Sultanates.[116] The empire reached its peak during the rule of Krishnadevaraya when Vijayanagara armies were consistently victorious.[117] The empire annexed areas formerly under the Sultanates in the northern Deccan and the territories in the eastern Deccan, including Kalinga, while simultaneously maintaining control over all its subordinates in the south.[118] It lasted until 1646, though its power declined after a major military defeat in 1565 by the Deccan sultanates. As a result, much of the territory of the former Vijaynagar Empire were captured by Deccan Sultanates, and the remainder was divided into many states ruled by Hindu rulers.

Delhi Sultanate[edit]

Main article: Delhi Sultanate

In the 12th and 13th centuries, Turks and Afghans invaded parts of northern India and established the Delhi Sultanate in the former Rajputholdings.[119] The subsequent Slave dynasty of Delhi managed to conquer large areas of northern India, approximately equal in extent to the ancient Gupta Empire, while the Khilji dynasty conquered most of central India but were ultimately unsuccessful in conquering and uniting the subcontinent. The Sultanate ushered in a period of Indian cultural renaissance. The resulting "Indo-Muslim" fusion of cultures left lasting syncretic monuments in architecture, music, literature, religion, and clothing. It is surmised that the language of Urdu (literally meaning "horde" or "camp" in various Turkic dialects) was born during the Delhi Sultanate period as a result of the intermingling of the local speakers of Sanskritic Prakrits with immigrants speaking Persian, Turkic, and Arabic under the Muslim rulers. The Delhi Sultanate is the only Indo-Islamic empire to enthrone one of the few female rulers in India, Razia Sultana (1236–1240).

A Turco-Mongol conqueror in Central Asia, Timur (Tamerlane), attacked the reigning Sultan Nasir-u Din Mehmud of the Tughlaq Dynasty in the north Indian city of Delhi.[120] The Sultan's army was defeated on 17 December 1398. Timur entered Delhi and the city was sacked, destroyed, and left in ruins, after Timur's army had killed and plundered for three days and nights. He ordered the whole city to be sacked except for the sayyids, scholars, and the other Muslims; 100,000 war prisoners were put to death in one day.[121]

Early modern period (1500-1850)[edit]

Mughal Empire[edit]

Main article: Mughal Empire

In 1526, Babur, a Timurid descendant of Timur and Genghis Khan from Fergana Valley(modern day Uzbekistan), swept across the Khyber Pass and established the Mughal Empire, covering modern day Afghanistan, Pakistan, India and Bangladesh.[122] However, his son Humayun was defeated by the Afghan warrior Sher Shah Suri in the year 1540, and Humayun was forced to retreat to Kabul. After Sher Shah's death, his son Islam Shah Suriand the Hindu king Samrat Hem Chandra Vikramaditya, who had won 22 battles against Afghan rebels and forces of Akbar, from Punjab to Bengal and had established a secularHindu rule in North India from Delhi till 1556. Akbar's forces defeated and killed Hemu in theSecond Battle of Panipat on 6 November 1556.

The Mughal dynasty ruled most of the Indian subcontinent by 1600; it went into a slow decline after 1707. The Mughals suffered sever blow due to invasions from Marathas and Afghans due to which the Mughal dynasty were reduced to puppet rulers by 1757. The remnants of the Mughal dynasty were finally defeated during the Indian Rebellion of 1857, also called the 1857 War of Independence. This period marked vast social change in the subcontinent as the Hindu majority were ruled over by the Mughal emperors, most of whom showed religious tolerance, liberally patronising Hindu culture. The famous emperor Akbar, who was the grandson of Babar, tried to establish a good relationship with the Hindus. However, later emperors such as Aurangazeb tried to establish complete Muslim dominance, and as a result several historical temples were destroyed during this period and taxes imposed on non-Muslims. During the decline of the Mughal Empire, several smaller states rose to fill the power vacuum and themselves were contributing factors to the decline. In 1739, Nader Shah, emperor of Iran, defeated the Mughal army at the huge Battle of Karnal. After this victory, Nader captured and sacked Delhi, carrying away many treasures, including the Peacock Throne.[123]

The Mughals were perhaps the richest single dynasty to have ever existed. During the Mughal era, the dominant political forces consisted of the Mughal Empire and its tributaries and, later on, the rising successor states - including the Maratha Empire - which fought an increasingly weak Mughal dynasty. The Mughals, while often employing brutal tactics to subjugate their empire, had a policy of integration with Indian culture, which is what made them successful where the short-lived Sultanates of Delhi had failed. Akbar the Great was particularly famed for this. Akbar declared "Amari" or non-killing of animals in the holy days of Jainism. He rolled back the jizya tax for non-Muslims. The Mughal emperors married local royalty, allied themselves with local maharajas, and attempted to fuse their Turko-Persian culture with ancient Indian styles, creating a unique Indo-Saracenic architecture. It was the erosion of this tradition coupled with increased brutality and centralization that played a large part in the dynasty's downfall after Aurangzeb, who unlike previous emperors, imposed relatively non-pluralistic policies on the general population, which often inflamed the majority Hindu population.

Post-Mughal period[edit]

Main articles: Maratha Empire, Kingdom of Mysore, Hyderabad State, Nawab of Bengal, Sikh Empire, Rajputs, and Durrani Empire

Further information: Shivaji, Tipu Sultan, Nizam, Nawab of Oudh, Ranjit Singh, and Ahmad Shah Abdali

Maratha Empire[edit]

Main article: Maratha Empire

The post-Mughal era was dominated by the rise of the Maratha suzerainty as other small regional states (mostly late Mughal tributary states) emerged, and also by the increasing activities of European powers (see colonial era below). There is no doubt that the single most important power to emerge in the long twilight of the Mughal dynasty was the Maratha Empire.[124] The Maratha kingdom was founded and consolidated by Shivaji, a Maratha aristocrat of the Bhonsle clan who was determined to establish Hindavi Swarajya (self-rule of Hindupeople). By the 18th century, it had transformed itself into the Maratha Empire under the rule of the Peshwas (prime ministers). Gordon explains how the Maratha systematically took control over the Malwa plateau in 1720-1760. They started with annual raids, collecting ransom from villages and towns while the declining Mughal Empire retained nominal control. However in 1737, the Marathas defeated a Mughal army in their capital, Delhi inteslf, and as a result, the Mughal emperor ceded Malwa to them. The Marathas continued their military campaigns against Mughals, Nizam, Nawab of Bengal and Durrani Empire to further extend their boundaries. They built an efficient system of public administration known for its attention to detail. It succeeded in raising revenue in districts that recovered from years of raids, up to levels previously enjoyed by the Mughals. The cornerstone of the Maratha rule in Malwa rested on the 60 or so local tax collectors (kamavisdars) who advanced the Maratha ruler '(Peshwa)' a portion of their district revenues at interest.[125] By 1760, the domain of the Marathas stretched across practically the entire subcontinent.[126] The defeat of Marathas by British in three Anglo-Maratha Wars brought end to the empire by 1820. The last peshwa, Baji Rao II, was defeated by the British in the Third Anglo-Maratha War.

Sikh Empire (North-west)[edit]

Main article: Sikh Empire

See also: History of Sikhism

The Punjabi kingdom, ruled by members of the Sikh religion, was a political entity that governed the region of modern-day Punjab. The empire, based around the Punjab region, existed from 1799 to 1849. It was forged, on the foundations of the Khalsa, under the leadership ofMaharaja Ranjit Singh (1780–1839) from an array of autonomous Punjabi Misls. He consolidated many parts of northern India into a kingdom. He primarily used his highly disciplined Sikh army that he trained and equipped to be the equal of a European force. Ranjit Singh proved himself to be a master strategist and selected well qualified generals for his army. In stages, he added the central Punjab, the provinces of Multan and Kashmir, the Peshawar Valley, and the Derajat to his kingdom. His came in the face of the powerful British East India Company.[127][128] At its peak, in the 19th century, the empire extended from the Khyber Pass in the west, to Kashmir in the north, toSindh in the south, and Himachal in the east. This was among the last areas of the subcontinent to be conquered by the British. The firstand second Anglo-Sikh war marked the downfall of the Sikh Empire.

Other kingdoms[edit]

There were several other kingdoms which ruled over parts of India in the later mediaeval period prior to the British occupation. However, most of them were bound to pay regular tribute to the Marathas.[126] The rule of Wodeyar dynasty which established the Kingdom of Mysore in southern India in around 1400 CE by was interrupted by Hyder Ali and his son Tipu Sultan in the later half of 18th century. Under their rule, Mysore fought a series of wars sometimes against the combined forces of the British and Marathas, but mostly against the British, with Mysore receiving some aid or promise of aid from the French.

The Nawabs of Bengal had become the de facto rulers of Bengal following the decline of Mughal Empire. However, their rule was interrupted by Marathas who carried six expeditions in Bengal from 1741 to 1748 as a result of which Bengal became a vassal state of Marathas.

Hyderabad was founded by the Qutb Shahi dynasty of Golconda in 1591. Following a brief Mughal rule, Asif Jah, a Mughal official, seized control of Hyderabad and declared himselfNizam-al-Mulk of Hyderabad in 1724. It was ruled by a hereditary Nizam from 1724 until 1948. Both Mysore and Hyderabad became princely states in British India.

Colonial era (1500-1947)[edit]

Main article: Colonial India

In 1498, Vasco da Gama successfully discovered a new sea route from Europe to India, which paved the way for direct Indo-European commerce.[129] The Portuguese soon set up trading posts in Goa, Daman, Diu and Bombay. The next to arrive were the Dutch, the British—who set up a trading post in the west coast port of Surat[130] in 1619—and the French. The internal conflicts among Indian kingdoms gave opportunities to the European traders to gradually establish political influence and appropriate lands. Although these continental European powers controlled various coastal regions of southern and eastern India during the ensuing century, they eventually lost all their territories in India to the British islanders, with the exception of the French outposts of Pondichéry and Chandernagore, the Dutch port of Travancore, and the Portuguese colonies of Goa, Daman and Diu.

Company rule in India[edit]

Main articles: East India Company and Company rule in India

In 1617 the British East India Company was given permission by Mughal Emperor Jahangir to trade in India.[131] Gradually their increasing influence led the de jure Mughal emperor Farrukh Siyar to grant them dastaks or permits for duty free trade in Bengal in 1717.[132] The Nawab of Bengal Siraj Ud Daulah, the de facto ruler of the Bengal province, opposed British attempts to use these permits.

The First Carnatic War extended from 1746 until 1748 and was the result of colonial competition between France and Britain, two of the countries involved in the War of Austrian Succession. Following the capture of a few French ships by the British fleet in India, French troops attacked and captured the British city of Madras located on the east coast of India on 21 September 1746. Among the prisoners captured at Madras was Robert Clive himself. The war was eventually ended by the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle which ended the War of Austrian Succession in 1748.

In 1749, the Second Carnatic War broke out as the result of a war between a son, Nasir Jung, and a grandson, Muzaffer Jung, of the deceased Nizam-ul-Mulk of Hyderabad to take over Nizam's throne in Hyderabad. The French supported Muzaffer Jung in this civil war. Consequently, the British supported Nasir Jung in this conflict.

Meanwhile, however, the conflict in Hyderabad provided Chanda Sahib with an opportunity to take power as the new Nawab of the territory of Arcot. In this conflict, the French supported Chandra Sahib in his attempt to become the new Nawab of Arcot. The British supported the son of the deposed incumbent Nawab, Anwaruddin Muhammad Khan, against Chanda Sahib. In 1751, Robert Clive led a British armed force and captured Arcot to reinstate the incumbent Nawab. The Second Carnatic War finally came to an end in 1754 with the Treaty of Pondicherry.

In 1756, the Seven Years War broke out between the great powers of Europe, and India became a theatre of action, where it was called the Third Carnatic War. Early in this war, armed forces under the French East India Company captured the British base of Calcutta in north-eastern India. However, armed forces under Robert Clive later recaptured Calcutta and then pressed on to capture the French settlement of Chandannagar in 1757. This led to the Battle of Plassey on 23 June 1757, in which the Bengal Army of the East India Company, led by Robert Clive, defeated the French-supported Nawab's forces. This was the first real political foothold with territorial implications that the British acquired in India. Clive was appointed by the company as its first 'Governor of Bengal' in 1757.[133] This was combined with British victories over the French at Madras, Wandiwash and Pondichérythat, along with wider British successes during the Seven Years War, reduced French influence in India. Thus as a result of the three Carnatic Wars, the British East India Company gained exclusive control over the entire Carnatic region of India.[134] The British East India Company extended its control over the whole of Bengal. After the Battle of Buxar in 1764, the company acquired the rights of administration in Bengal from Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II; this marked the beginning of its formal rule, which within the next century engulfed most of India and extinguished the Moghul rule and dynasty.[135] The East India Company monopolized the trade of Bengal. They introduced a land taxation system called the Permanent Settlement which introduced a feudal-like structure in Bengal, often with zamindars set in place. By the 1850s, the East India Company controlled most of the Indian sub-continent, which included present-day Pakistan and Bangladesh. Their policy was sometimes summed up as Divide and Rule, taking advantage of the enmity festering between various princely states and social and religious groups.[136]

The Hindu Ahom Kingdom of North-east India first fell to Burmese invasion and then to British after Treaty of Yandabo in 1826.

The rebellion of 1857 and its consequences[edit]

Main article: Indian rebellion of 1857

The Indian rebellion of 1857 was a large-scale rebellion by soldiers employed by the British East India in northern and central India against the Company's rule. The rebels were disorganized, had differing goals, and were poorly equipped, led, and trained, and had no outside support or funding. They were brutally suppressed and the British government took control of the Company and eliminated many of the grievances that caused it. The government also was determined to keep full control so that no rebellion of such size would ever happen again. It favoured the princely states (that helped suppress the rebellion), and tended to favour Muslims (who were less rebellious) against the Hindus who dominated the rebellion.[137]

In the aftermath, all power was transferred from the East India Company to the British Crown, which began to administer most of India as a number of provinces; the John Company's lands were controlled directly, while it had considerable indirect influence over the rest of India, which consisted of the Princely states ruled by local royal families. There were officially 565 princely states in 1947, but only 21 had actual state governments, and only three were large (Mysore, Hyderabad and Kashmir). They were absorbed into the independent nation in 1947-48.[138]

British Raj (1858-1947)[edit]

Main article: British Raj

Reforms[edit]

When the Lord Curzon (Viceroy 1899-1905) took control of higher education and then split the large province of Bengal into a largely Hindu western half and "Eastern Bengal and Assam," a largely Muslim eastern half. The British goal was efficient administration but Hindus were outraged at the apparent "divide and rule" strategy." When the Liberal party in Britain came to power in 1906 he was removed. The new Viceroy Gilbert Minto and the new Secretary of State for India John Morley consulted with Congress leader Gopal Krishna Gokhale. The Morley-Minto reforms of 1909 provided for Indian membership of the provincial executive councils as well as the Viceroy's executive council. The Imperial Legislative Council was enlarged from 25 to 60 members and separate communal representation for Muslims was established in a dramatic step towards representative and responsible government. Bengal was reunified in 1911.[139] Meanwhile the Muslims for the first time began to organise, setting up the All India Muslim League in 1906. It was not a mass party but was designed to protect the interests of the aristocratic Muslims, especially in the north west. It was internally divided by conflicting loyalties to Islam, the British, and India, and by distrust of Hindus.[140]

Famines[edit]

During the British Raj, famines in India, often attributed to failed government policies, were some of the worst ever recorded, including the Great Famine of 1876–78 in which 6.1 million to 10.3 million people died[141] and the Indian famine of 1899–1900 in which 1.25 to 10 million people died.[141] The Third Plague Pandemic started in China in the middle of the 19th century, spreading plague to all inhabited continents and killing 10 million people in India alone.[142] Despite persistent diseases and famines, the population of the Indian subcontinent, which stood at about 125 million in 1750, had reached 389 million by 1941.[143]

The Indian independence movement[edit]

Main articles: Indian independence movement and Pakistan Movement

See also: Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and Indian independence activists

The numbers of British in India were small, yet they were able to rule two-thirds of the subcontinent directly and exercise considerable leverage over the princely states that accounted for the remaining one-third of the area. There were 674 of the these states in 1900, with a population of 73 million, or one person in five. In general, the princely states were strong supporters of the British regime, and the Raj left them alone. They were finally closed down in 1947-48.[144]

The first step toward Indian self-rule was the appointment of councillors to advise the British viceroy, in 1861; the first Indian was appointed in 1909. Provincial Councils with Indian members were also set up. The councillors' participation was subsequently widened into legislative councils. The British built a large British Indian Army, with the senior officers all British, and many of the troops from small minority groups such as Gurkhas from Nepal and Sikhs. The civil service was increasingly filled with natives at the lower levels, with the British holding the more senior positions.[145]

From 1920 leaders such as Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi began highly popular mass movements to campaign against the British Raj using largely peaceful methods. Some others adopted a militant approach that sought to overthrow British rule by armed struggle;revolutionary activities against the British rule took place throughout the Indian sub-continent. The Gandhi-led independence movement opposed the British rule using non-violent methods like non-cooperation, civil disobedience and economic resistance. These movements succeeded in bringing independence to the new dominions of India and Pakistan in 1947.

Independence and partition (1947-present)[edit]

Main articles: Partition of India, History of the Republic of India, History of Pakistan, and History of Bangladesh

Along with the desire for independence, tensions between Hindus and Muslims had also been developing over the years. The Muslims had always been a minority within the subcontinent, and the prospect of an exclusively Hindu government made them wary of independence; they were as inclined to mistrust Hindu rule as they were to resist the foreign Raj, although Gandhi called for unity between the two groups in an astonishing display of leadership. The British, extremely weakened by the Second World War, promised that they would leave and participated in the formation of an interim government. The British Indian territories gained independence in 1947, after being partitioned into the Union of Indiaand Dominion of Pakistan. Following the controversial division of pre-partition Punjab and Bengal, rioting broke out between Sikhs, Hindus and Muslims in these provinces and spread to several other parts of India, leaving some 500,000 dead.[146] Also, this period saw one of the largest mass migrations ever recorded in modern history, with a total of 12 million Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims moving between the newly created nations of India and Pakistan (which gained independence on 15 and 14 August 1947 respectively).[146] In 1971, Bangladesh, formerly East Pakistan and East Bengal, seceded from Pakistan.

Historiography[edit]

In recent decades there have been four main schools of historiography regarding India: Cambridge, Nationalist, Marxist, and subaltern. The once common "Orientalist" approach, with its the image of a sensuous, inscrutable, and wholly spiritual India, has died out in serious scholarship.[147]

The "Cambridge School," led by Anil Seal,[148] Gordon Johnson,[149] Richard Gordon, and David A. Washbrook,[150] downplays ideology.[151]

The Nationalist school has focused on Congress, Gandhi, Nehru and high level politics. It highlighted the Mutiny of 1857 as a war of liberation, and Gandhi's 'Quit India' begun in 1942, as defining historical events. More recently, Hindu nationalists have created a version of history for the schools to support their demands for "Hindutva" ("Hinduness") in Indian society.[152]

The Marxists have focused on studies of economic development, landownership, and class conflict in precolonial India and of deindustrialization during the colonial period. The Marxists portrayed Gandhi's movement as a device for the bourgeois elite to harness popular, potentially revolutionary forces for its own ends.[153]

The "subaltern school," was begun in the 1980s by Ranajit Guha and Gyan Prakash.[154] It focuses attention away from the elites and politicians to "history from below," looking at the peasants using folklore, poetry, riddles, proverbs, songs, oral history and methods inspired by anthropology. It focuses on the colonial era before 1947 and typically emphasizes caste and downplays class, to the annoyance of the Marxist school.[155]

Economy of India

he economy of India is the ninth-largest in the world by nominal GDP and the third-largest by purchasing power parity(PPP).[1] The country is one of the G-20 major economies and a member of BRICS. On a per-capita-income basis, India ranked141st by nominal GDP and 130th by GDP (PPP) in 2012, according to the IMF.[14] India is the 19th-largest exporter and the10th-largest importer in the world. Economic growth rate slowed to around 5.0% for the 2012–13 fiscal year compared with 6.2% in the previous fiscal.[15] It is to be noted that India's GDP grew by an astounding 9.3% in 2010–11. Thus, the growth rate has nearly halved in just three years. GDP growth went up marginally to 4.8% during the quarter through March 2013, from about 4.7% in the previous quarter. The government has forecasted a growth of 6.1%-6.7% for the year 2013-14, whilst the RBI expects the same to be at 5.7%.

The independence-era Indian economy (from 1947 to 1991) was based on a mixed economy combining features of capitalism and socialism, resulting in an inward-looking, interventionist policies and import-substituting economy that failed to take advantage of the post-war expansion of trade.[16] This model contributed to widespread inefficiencies and corruption, and the failings of this system were due largely to its poor implementation.[16]

In 1991, India adopted liberal and free-market principles and liberalized its economy to international trade under the guidance ofP.V. Narasimha Rao, prime minister from 1991 to 1996, who had eliminated License Raj, a pre- and post-British era mechanism of strict government controls on setting up new industry. Following these major economic reforms, and a strong focus on developing national infrastructure such as the Golden Quadrilateral project by Atal Bihari vajpayee, prime minister, the country's economic growth progressed at a rapid pace, with relatively large increases in per-capita incomes.[17]

| Economy of India | |

|---|---|

Mumbai, The entertainment, fashion, and commercial centre of India | |

| Rank | 10th (nominal) / 3rd (PPP) |

| Currency | 1 (INR) ( |

| Fiscal year | 1 April – 31 March |

| Trade organizations | WTO, SAFTA, G-20 and others |

| Statistics | |

| GDP | $4.684 trillion (PPP: 3rd; 2012)[1] |

| GDP growth | 6.5% (2012 est) |

| GDP per capita | $3,829 (PPP: 130th; 2012)[1] |

| GDP by sector | agriculture: 17.2%, industry: 26.4%,services: 56.4% (2011 est.) |

| Inflation (CPI) | CPI: 9.31%, WPI: 4.7% (April 2013) |

| Population below poverty line | 29.8% (2010) |

| Gini coefficient | 36.8 (List of countries) |

| Labour force | 498.4 million (2012 est.) |

| Labour force by occupation | agriculture: 53%, industry: 19%,services: 28% (2011 est.) |

| Unemployment | 3.8% (2011 est.)[2] |

| Average gross salary | $1,410 yearly (2011)[3] |

| Main industries | textiles, chemicals, food processing,steel, transportation equipment, cement,mining, petroleum, machinery, software,pharmaceuticals |

| Ease of Doing Business Rank | 132nd[4] (2012) |

| External | |

| Exports |

$142 billion (2012 est.)

[5] |

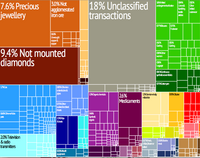

| Export goods | petroleum products, precious stones,machinery, iron and steel, chemicals,vehicles, apparel |

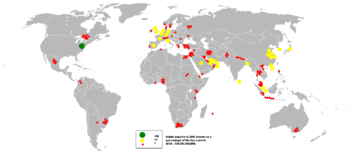

| Main export partners | |

| Imports | $235 billion (2012 est.) [7] |

| Import goods | crude oil, raw precious stones, machinery, fertilizer, iron and steel,chemicals |

| Main import partners | |

| FDI stock | $47 billion (2011–12)[9] |

| Gross external debt | $299.2 billion (31 December 2012) |

| Public finances | |

| Public debt | 67.59% of GDP (2012 est.)[10] |

| Budget deficit | 5.2% of GDP (2011–12) |

| Revenues | $171.5 billion billion (2012 est.) |

| Expenses | $281 billion billion (2012 est.) |

| Economic aid | $2.107 billion (2008)[11] |

| Credit rating | BBB- (Domestic) BBB- (Foreign) BBB+ (T&C Assessment) Outlook: Stable (Standard & Poor's)[12] |

| Foreign reserves | $295.29 billion (October 2012)[13] |

|

| |

History[edit]

Main articles: Economic history of India and Timeline of the economy of India

Pre-colonial period (up to 1773)[edit]

The citizens of the Indus Valley civilisation, a permanent settlement that flourished between 2800 BC and 1800 BC, practiced agriculture, domesticated animals, used uniform weights and measures, made tools and weapons, and traded with other cities. Evidence of well-planned streets, a drainage system and water supply reveals their knowledge of urban planning, which included the world's first urban sanitation systems and the existence of a form of municipal government.[23]

Maritime trade was carried out extensively between South India and southeast and West Asia from early times until around the fourteenth century AD. Both the Malabar and Coromandel Coasts were the sites of important trading centres from as early as the first century BC, used for import and export as well as transit points between the Mediterranean region and southeast Asia.[25] Over time, traders organised themselves into associations which received state patronage. Raychaudhuri and Habib claim this state patronage for overseas trade came to an end by the thirteenth century AD, when it was largely taken over by the local Parsi, Jewish and Muslim communities, initially on the Malabar and subsequently on the Coromandel coast.[26]

Other scholars suggest trading from India to West Asia and Eastern Europe was active between 14th and 18th century.[27][28][29] During this period, Indian traders had settled in Surakhani, a suburb of greater Baku, Azerbaijan. These traders had built a Hindu temple, now preserved by the government of Azerbaijan. French Jesuit Villotte, who lived in Azerbaijan in late 1600s, wrote this Indian temple was revered by Hindus;[30] the temple has numerous carvings in Sanskrit or Punjabi, dated to be between 1500 and 1745 AD. The Atashgah temple built by the Baku-resident traders from India suggests commerce was active and prosperous for Indians by the 17th century.[31][32][33][34]

Further north, the Saurashtra and Bengal coasts played an important role in maritime trade, and theGangetic plains and the Indus valley housed several centres of river-borne commerce. Most overland trade was carried out via the Khyber Pass connecting the Punjab region with Afghanistan and onward to the Middle East and Central Asia.[35] Although many kingdoms and rulers issued coins, barter was prevalent. Villages paid a portion of their agricultural produce as revenue to the rulers, while their craftsmen received a part of the crops at harvest time for their services.[36]

Sean Harkin estimates China and India may have accounted for 60 to 70 percent of world GDP in the 17th century.[37]

Assessment of India's pre-colonial economy is mostly qualitative, owing to the lack of quantitative information. The Mughal economy functioned on an elaborate system of coined currency, land revenue and trade. Gold, silver and copper coins were issued by the royal mints which functioned on the basis of free coinage.[38] The political stability and uniform revenue policy resulting from a centralised administration under the Mughals, coupled with a well-developed internal trade network, ensured that India, before the arrival of the British, was to a large extent economically unified, despite having a traditional agrarian economy characterised by a predominance of subsistence agriculture dependent on primitive technology.[39] After the decline of theMughals, western, central and parts of south and north India were integrated and administered by the Maratha Empire. After the loss at the Third Battle of Panipat, the Maratha Empire disintegrated into several confederate states, and the resulting political instability and armed conflict severely affected economic life in several parts of the country, although this was compensated for to some extent by localised prosperity in the new provincial kingdoms.[40] By the end of the eighteenth century, the British East India Company entered the Indian political theatre and established its dominance over other European powers. This marked a determinative shift in India's trade, and a less powerful impact on the rest of the economy.[41]

Colonial period (1773–1947)[edit]

There is no doubt that our grievances against the British Empire had a sound basis. As the painstaking statistical work of the Cambridge historian Angus Maddison has shown, India's share of world income collapsed from 22.6% in 1700, almost equal to Europe's share of 23.3% at that time, to as low as 3.8% in 1952. Indeed, at the beginning of the 20th century, "the brightest jewel in the British Crown" was the poorest country in the world in terms of per capita income.

"I have travelled across the length and breadth of India and I have not seen one person who is a beggar, who is a thief. Such wealth I have seen in this country, such high moral values, people of such calibre, that I do not think we would ever conquer this country, unless we break the very backbone of this nation, which is her spiritual and cultural heritage, and, therefore, I propose that we replace her old and ancient education system, her culture, for if the Indians think that all that is foreign and English is good and greater than their own, they will lose their self-esteem, their native culture and they will become what we want them, a truly dominated nation." | Lord T. B. Macaulay's address to British Parliament, dated the 2nd February 1835.

Company rule in India brought a major change in the taxation and agricultural policies, which tended to promote commercialisation of agriculture with a focus on trade, resulting in decreased production of food crops, mass impoverishment and destitution of farmers, and in the short term, led to numerous famines.[43] The economic policies of the British Rajcaused a severe decline in the handicrafts and handloom sectors, due to reduced demand and dipping employment.[44] After the removal of international restrictions by the Charter of 1813, Indian trade expanded substantially and over the long term showed an upward trend.[45] The result was a significant transfer of capital from India to England, which, due to the colonial policies of the British, led to a massive drain of revenue rather than any systematic effort at modernisation of the domestic economy.[46]

India's colonisation by the British created an institutional environment that, on paper, guaranteed property rights among the colonisers, encouraged free trade, and created a single currency with fixed exchange rates, standardised weights and measures and capital markets. It also established a well-developed system of railways and telegraphs, a civil service that aimed to be free from political interference, a common-law and an adversarial legal system.[48] This coincided with major changes in the world economy – industrialisation, and significant growth in production and trade. However, at the end of colonial rule, India inherited an economy that was one of the poorest in the developing world,[49] with industrial development stalled, agriculture unable to feed a rapidly growing population, a largely illiterate and unskilled labour force, and extremely inadequate infrastructure.[50]

The 1872 census revealed that 91.3% of the population of the region constituting present-day India resided in villages,[51] and urbanisation generally remained sluggish until the 1920s, due to the lack of industrialisation and absence of adequate transportation. Subsequently, the policy of discriminating protection (where certain important industries were given financial protection by the state), coupled with the Second World War, saw the development and dispersal of industries, encouraging rural-urban migration, and in particular the large port cities of Bombay, Calcuttaand Madras grew rapidly. Despite this, only one-sixth of India's population lived in cities by 1951.[52]

The impact of British occupation on India's economy is a controversial topic. Leaders of the Indian independence movement and economic historians have blamed colonial occupation for the dismal state of India's economy in its aftermath and argued that financial strength required for industrial development in Europe was derived from the wealth taken from colonies in Asia and Africa. At the same time, right-wing historians have countered that India's low economic performance was due to various sectors being in a state of growth and decline due to changes brought in by colonialism and a world that was moving towards industrialisation and economic integration.[53]

Pre-liberalisation period (1947–1991)[edit]

Indian economic policy after independence was influenced by the colonial experience, which was seen by Indian leaders as exploitative, and by those leaders' exposure to British social democracy as well as the progress achieved by the planned economy of the Soviet Union.[50] Domestic policy tended towards protectionism, with a strong emphasis onimport substitution industrialisation, economic interventionism, a large public sector, business regulation, and central planning,[54] while trade and foreign investment policies were relatively liberal.[55] Five-Year Plans of India resembled central planning in the Soviet Union. Steel, mining, machine tools, telecommunications, insurance, and power plants, among other industries, were effectively nationalised in the mid-1950s.[56]

| “ | Never talk to me about profit, Jeh, it is a dirty word. | ” |

—Nehru, India's Fabian Socialism inspired first prime minister to industrialist J.R.D. Tata, when Tata suggested state-owned companies should be profitable, [57]

| ||

Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India, along with the statistician Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis, formulated and oversaw economic policy during the initial years of the country's independence. They expected favorable outcomes from their strategy, involving the rapid development of heavy industry by both public and private sectors, and based on direct and indirect state intervention, rather than the more extreme Soviet-style central command system.[58][59] The policy of concentrating simultaneously on capital- and technology-intensive heavy industry and subsidising manual, low-skill cottage industries was criticised by economist Milton Friedman, who thought it would waste capital and labour, and retard the development of small manufacturers.[60] The rate of growth of the Indian economy in the first three decades after independence was derisively referred to as the Hindu rate of growth by economists, because of the unfavourable comparison with growth rates in other Asian countries.[61][62]

| “ | (In the current Indian regulatory system,) I cannot decide how much to borrow, what shares to issue, at what price, what wages and bonus to pay, and what dividend to give. I even need the government's permission for the salary I pay to a senior executive. | ” |

—J. R. D. Tata in 1969, [57]

| ||

Since 1965, the use of high-yielding varieties of seeds, increased fertilisers and improved irrigation facilities collectively contributed to the Green Revolution in India, which improved the condition of agriculture by increasing crop productivity, improving crop patterns and strengthening forward and backward linkages between agriculture and industry.[63] However, it has also been criticised as an unsustainable effort, resulting in the growth of capitalistic farming, ignoring institutional reforms and widening income disparities.[64]

Subsequently the Emergency and Garibi Hatao concept under which income tax levels at one point rose to a maximum of 97.5%, a record in the world for non-communist economies, started diluting the earlier efforts.

Post-liberalisation period (since 1991)[edit]

Main articles: Economic liberalisation in India and Economic development in India

In the late 1970s, the government led by Morarji Desai eased restrictions on capacity expansion for incumbent companies, removed price controls, reduced corporate taxes and promoted the creation of small scale industries in large numbers. However, the subsequent government policy of Fabian socialism hampered the benefits of the economy, leading to high fiscal deficits and a worsening current account. The collapse of the Soviet Union, which was India's major trading partner, and the Gulf War, which caused a spike in oil prices, resulted in a major balance-of-payments crisis for India, which found itself facing the prospect of defaulting on its loans.[65] India asked for a $1.8 billion bailout loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which in return demanded reforms.[66]

In response, Prime Minister Narasimha Rao, along with his finance minister Manmohan Singh, initiated the economic liberalisation of 1991. The reforms did away with the Licence Raj, reduced tariffs and interest rates and ended many public monopolies, allowing automatic approval of foreign direct investment in many sectors.[67] Since then, the overall thrust of liberalisation has remained the same, although no government has tried to take on powerful lobbies such as trade unions and farmers, on contentious issues such as reforming labour laws and reducing agricultural subsidies.[68] By the turn of the 21st century, India had progressed towards a free-market economy, with a substantial reduction in state control of the economy and increased financial liberalisation.[69] This has been accompanied by increases in life expectancy, literacy rates and food security, although urban residents have benefited more than agricultural residents.[70]

While the credit rating of India was hit by its nuclear weapons tests in 1998, it has since been raised to investment level in 2003 by S&P and Moody's.[71] In 2003, Goldman Sachspredicted that India's GDP in current prices would overtake France and Italy by 2020, Germany, UK and Russia by 2025 and Japan by 2035, making it the third largest economy of the world, behind the US and China. India is often seen by most economists as a rising economic superpower and is believed to play a major role in the global economy in the 21st century.[72][73]

Sectors[edit]

Industry and services[edit]